The Secret to a Healthy Back

The problem with our bodies is that they’re so gosh-darn complex. From your head to the toes, there are a bunch of joints and muscles and stuff going on. How do we keep track of it all while we’re exercising? With so much complexity, we have to understand which structures are the most important and then prioritize using those structures with optimal biomechanics.

QUESTION: What’s our number one, most important structure in the body?

ANSWER: The Spine.

Comedian Hannibal Buress states it perfectly. “I don’t know if you know this about your back but... it’s most of your body. So if your back hurts your life sucks until your back doesn't hurt anymore.” Truer words have never been spoken. The spine is the base structure of your body. It is the center from which everything branches off, and contains that kinda-sorta important thing called your spinal cord. It also houses your nerve roots, which account for all the sensations and muscular actions you undergo. Simply put, if you had to treat only one structure well, it should be your spine. So… how do we treat it well?

Remember that the spine is a stable structure. I know what you’re thinking, “But Sam, that cool graphic clearly shows that the thoracic spine is mobile!” Yes, the thoracic spine does account for some mobility, and we will talk about that eventually, but for now let’s be naughty and say that the spine’s primary function is stability (maintaining one position or undergoing controlled, minute movements). By maintaining a stable spine two things happen. Firstly, on the performance side, we give our mobile joints a stable base from which to operate. Analogy: Think of your body as a car. The spine is the chassis, and your hips and shoulders are the back and front wheels. If that chassis isn’t rock solid, it doesn’t matter how powerful the engine is, some of that horsepower will be lost as its channeled to the wheels. Same thing with the spine. If the spine isn’t stable, the shoulders and hips can’t deliver as much power to the arms and legs.

Secondly, on the injury side, by maintaining a stable spine we minimize wear on the spinal structures (vertebrae, discs, nerve roots, facet joints, etc.), creating less pain and more longevity. Think of it this way. Each segment of your spine has two vertebrae with a disc in between. Everytime those vertebrae move back and forth, they grind down the disc. Eventually that disc will wear out completely, at which point you get herniations, nerve compression, and a bunch of other bad stuff. Additionally, there are structures on the back of your vertebrae that impinge on each other with extension, which causes even more issues.

Movement in the spine creates instability, leading to disc degeneration and a host of other problems.

All of this taken into account, here are our two laymen’s laws of spinal biomechanics:

Your spine likes a neutral position.

Your spine doesn’t like to move from that neutral position, i.e. it likes to remain stable.

A neutral spine position is one in which the pelvis, rib cage, and head are vertically aligned with one another, with approximately one hand-width of low back curvature. In this position, the vertebrae are symmetrically stacked with full surface area contact, allowing for the most efficient transfer of force through the spine.

Upon losing a neutral position (i.e. getting hyper-flexed or extended in one of the curves), the vertebrae become asymmetrically stacked, generating uneven wear on the spine and crappy positioning for the shoulders and hips. As such, it is our primary priority to maintain a neutral spine position throughout all movement, especially exercises in the gym.

A neutral position allows for efficient loading of the vertebrae and discs, preventing degeneration, nerve root impingement, and more.

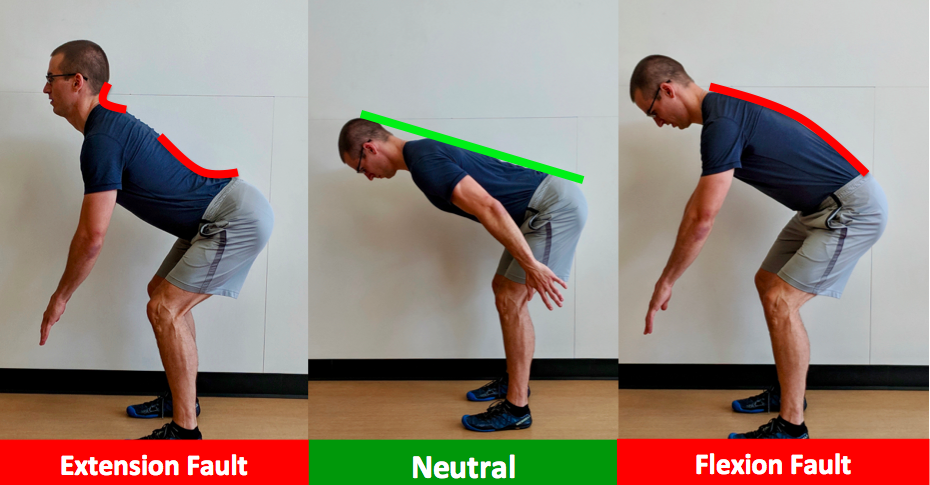

Now let's apply this to a basic exercise, a hip hinge. Notice that all three hip hinge variations look similar. It's small differences in spine position that make the middle hinge right and the outside two wrong. This brings to light that correcting biomechanics is usually a matter of very minute changes in position. Though these changes are minor don't let that allow you to think that they are insignificant. Over time, consistently hingeing with these bad spine positions will lead to back pain and possibly spine surgery. It's just so much simpler to be proactive and fix the movement mechanics instead of retroactively dealing with pain and surgery. Point being: Yes, these changes are subtle, but they are also very significant.

Hopefully that makes sense. Now, I’m going to finish this article with a statement you won’t like:

Crunches, back extensions, lateral crunches, and any other “core” exercises that take you out of a neutral spine position should be cut from your program immediately.

What? No crunches?! How am I going to work my core?!?!?!?!?!?! Answer: Isometrically. Your core is meant to hold your spine in a stable position as outside forces try to change that position. It is not meant to move your spine through a range of motion, creating all of the problems that we’ve already talked about. “But Sam, everyone does crunches. They’ve been around forever, they can’t be that bad.” Yes, they can be. Remember, exercise was originally thought of as a way to enhance aesthetics, not structural function. Crunches, back extensions, etc. do make trunk muscles bigger, just at the expense of your spine. We can work these trunk muscles more effectively with isometric exercises performed in a neutral spine position.

Do’s:

BIRDDOGS

PLANKS

PALLOF PRESSES

Don’ts:

CRUNCHES

BACK EXTENSIONS

LATERAL CRUNCH

I could rant all day on this, but I don’t have time and other professionals have laid it out more elegantly. If you don’t believe a word I’m saying, please read the work of Dr. Stuart McGill, the foremost authority on spine mechanics. His books Low Back Disorders and The Back Mechanic quantify the harm done by non-neutral positions with peer-reviewed research. Believe me, smarter people than I have figured out that this sh*t is true.

There you have it. A neutral spine position is the primary biomechanic that we must prioritize in movement. Doing so prevents unnecessary injury and sets a stable base from which the rest of our body can efficiently function. This article is a very surface-level overview of spine mechanics. To learn more about how to create, maintain, and train proper spine mechanics I’d suggest checking out our movement guide, Movement 101.